The Local Correspondent

In the 1940s and 1950s, journalist Laurose Wilkens set the standard for writing about Gilmanton

In the 1940s and 1950s, though, this town had a local correspondent who broke the mold. In her twice-weekly columns for The Laconia Citizen, Laurose Wilkens (1913-2007) brought Gilmanton to life as a novelist might, as a remote hill town filled with indelible and idiosyncratic characters. She wrote, for example, of a nameless farmer who evolved the perfect method for calming a riled pig. “He was found in the barn,” Laurose wrote, “with several quarts of motor oil, which he was busily pouring over the pigs.”

When Laurose marked August 1 one year, the halfway point of summer, there was music in her voice. “Gilmanton is so busy,” she wrote, “with the hum of tractors drifting on the air, and bales of hay dotting the fields. … Everyone, stuffed with strawberries from the first treasured crop, is now harvesting peas and beans, lettuce, squash and early corn, and the blueberries are ready too.”

She evoked a Gilmanton that is no longer. The town’s population was 700 in her day, and the box supper at the Grange Hall constituted the height of the social season. I’ve come across her writing here and there over the decades, researching Gilmanton, and it’s always made me feel wistful. And also curious. Who was this woman?

Last month, I crossed town to visit Laurose’s daughter, Joanne Wilkens, and as we sat by the woodstove, Joanne told me her mother grew up very wealthy, in Brooklyn. Her father was an importer of essential oils and her mother an opera singer who, early in life, had a contract performing at the Royal Opera House, in Berlin, Germany. When Laurose was three, her younger sister died of scarlet fever. After that, Joanne told me, “Her mother hovered over her. She bought her silk dresses and put bows in her hair as though they lived in Buckingham Palace. I think she felt trapped.”

Laurose went to Barnard College, an elite women’s school in Manhattan, then got married. In 1945, her husband William, an electrical engineer, ended up getting a job in New Hampshire. The couple bought a 200-acre hilltop farm in Gilmanton and appointed it with chickens and pigs. Laurose named one sheep Cornelia, after a famous Roman matron who lived in the second century BC. Almost every day, says Joanne, she eschewed a bra: “She dressed in blue jeans, a man’s white shirt and thong sandals. Here in Gilmanton, she found a certain kind of self-expression that she was not allowed to have as a child.”

When Joanne showed me a large scrapbook containing 60 or so of Laurose’s columns, I heard in the writer’s voice the delight of a newcomer to northern New England. In 1947, she wrote of deer season as “one of the most astounding spectacles this city-bred correspondent has ever witnessed. For 31 days, the little town of Gilmanton has been under a spell. Life came to a complete stand-still … while every single man who was physically able even to walk snatched his gun and vanished into that special world in which deer hunters live, and from which they emerge in crowds every now and then to swallow cups of coffee, consume doughnuts and an occasional egg.”

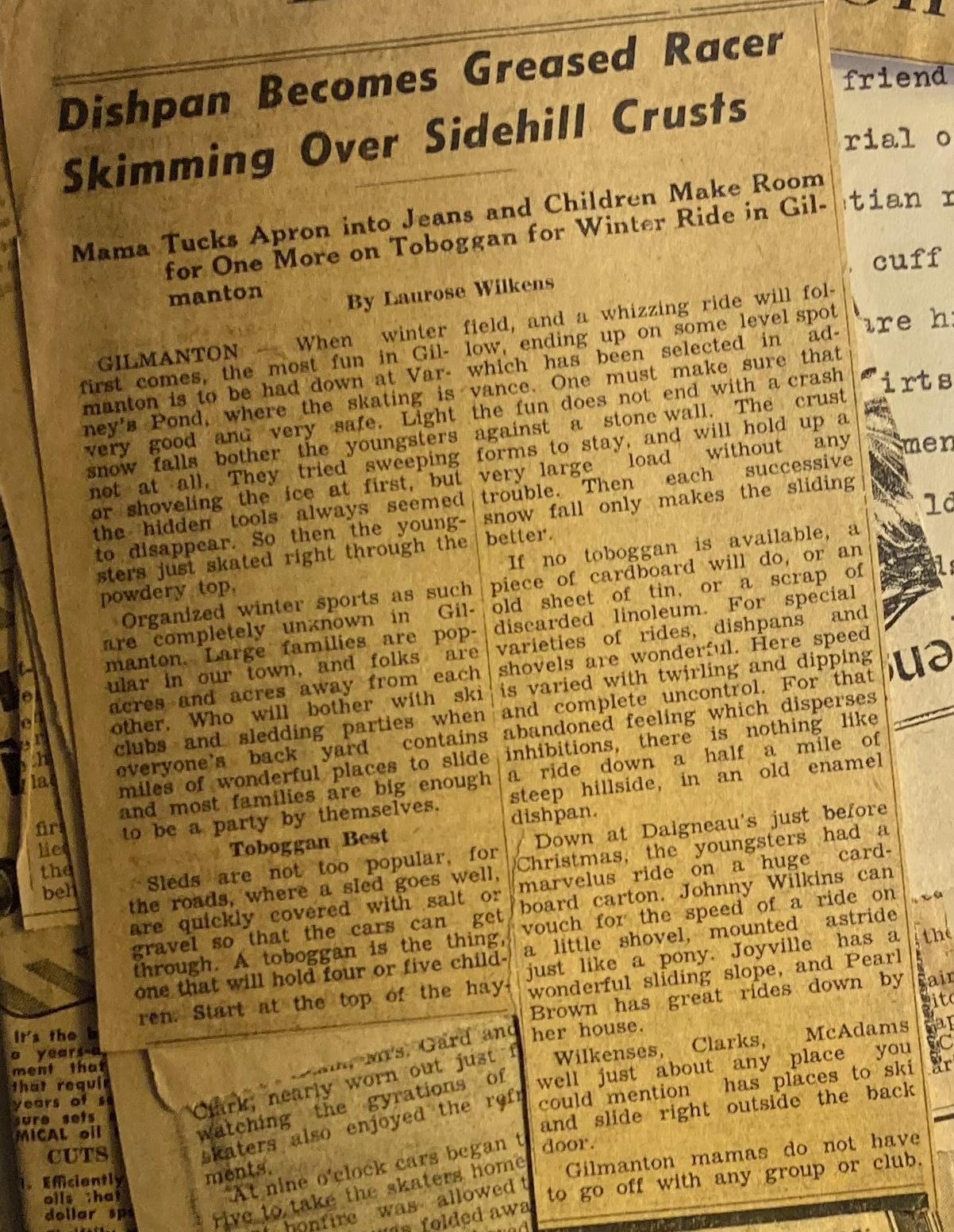

She was a champion of simple country pleasures, so that when winter came in 1950, she wrote, “The most fun in Gilmanton is to be had down at Varney’s Pond, where the skating is very good and very safe. … Organized winter sports are completely unknown in Gilmanton. Who will bother with ski clubs and sledding parties when everyone’s backyard contains miles of wonderful places to slide?”

There was, I believe, a political tilt to Laurose’s writing. She was rebelling against the hifalutin ways of her class and bringing to light the dignity of the folks who lived here. When she writes of a circa 1950 housewarming party that neighbors threw for Gilmanton residents Jane and Carl Moorhead, the story concludes, “The gentle ladies who engineered the evening did not leave without one final penetrating inspection to make sure that they had not forgotten one crumb that could be cleaned up.”

In one article, Laurose explained why she loved country people. “Folks in our towns,” she said, “are always so much themselves, the strange things they do and say being in perfect keeping with their personalities. The summer folks,” she continued, “seem more of a fold.” In Laurose’s eyes, they were all the same, and they were witless. When a moose wandered into Gilmanton Corners one year, she dryly sniped that it “gave the passing Massachusetts cars a real idea of the variety of life in Granite State villages.”

Laurose favored the local over the flatlander and the practical over the romantical. This becomes clear when you compare her to another chronicler of New England country life, E.B. White, who in 1952 published a beloved children’s novel, Charlotte’s Web, about a farm. White was a New Yorker who summered in Brooklin, Maine. His story centers on a pig, Wilbur, who improbably escapes butchery not once but twice. “Mr. Zuckerman,” White writes, alluding to the pig’s owner near the book’s end, “took fine care of Wilbur all the rest of his days.”

In 1949, Laurose wrote her own story about a pig, Wandering Walter, whom she owned. In her Citizen column, she describes her young son, Johnny, watching in horror as Walter is corralled into a butcher’s truck. “Surely never before in history have such bloodcurdling screeching sounded from the old red barn,” she says. “Walter protested at the top of his lungs.” Then, eventually, “astounded spectators heard howls almost equally loud from a new source”—Johnny. The kid is aghast that the family pig is about to be slaughtered, but no one accedes to his sentimentality. The pig is summarily killed, and still somehow Laurose delivers us grace: “With kindly understanding, the butcher discussed the situation with the weeping warrior. … Peace was soon restored. John and the butcher departed friends.”

Paid 20 or 25 dollars a week for her work, Laurose wrote her stories in her kitchen, her typewriter set atop a low pullout desk as, Joanne says, “All five of us children were running around her.” Sometimes to meet a tight deadline, she wrote her stories while parked just outside The Citizen’s office in Laconia, “in the Pontiac,” Joanne remembers, with the typewriter on her knees. If we’d bother her, she’d say, ‘Here’s a dollar. Now go over to Bill’s Diner and get yourself a Pepsi.”

In an era before influencers and Tik Tok celebrities, Laurose’s take on things mattered. Shoe saleswomen at O’Shea’s, in Laconia, awaited her next column, and The Citizen, knowing that her name sold papers, ran it in headlines: “Laurose Wilkens Looks In On Summer in Gilmanton.” When she briefly moved to Rhode Island in the 1950s, the paper still enlisted her to file dispatches on how much she missed home: “Gilmanton Christmas as Pictured by Laurose Wilkens in Rhode Island.”

In the early 1960s, Laurose stopped writing when tragedy struck her twice in quick succession. In 1960, her son Billy, a track and basketball star, died at age 20 of osteosarcoma after losing a leg to the disease. For a dozen years, as she grieved, Laurose kept Billy’s prosthetic leg in her house in Gilmanton. “It was just part of the family,” says Joanne. “Like you could just look at it and say, ‘Goodnight, leg.’ But then in about 1972 I saw my mother carrying the leg out to the white barn to store in the attic, and I just said to myself, “Well, at last she’s at peace with Billy’s death.”

In middle age, Laurose worked as a teacher. After that, she ran a dog kennel at her hilltop home. She became a grandmother, then a great-grandmother. But she never wrote about Gilmanton again. Indeed, she did not write much at all. In her columns, she had captured a specific moment in the town’s history. She had recorded the life of a place she loved with brio and style. What more was there for her to say?

Readers, please support local journalism! I am now resolved to keeping this newsletter free to all, but I honestly cannot keep filing in-depth reports without further funding. If you’re able, please consider becoming a paid subscriber. If you can’t figure out how to subscribe—the technology is daunting!—write me at billdonahuewriter@gmail.com and I can render assistance.

Was her farm where Gilmanton's Own is now?